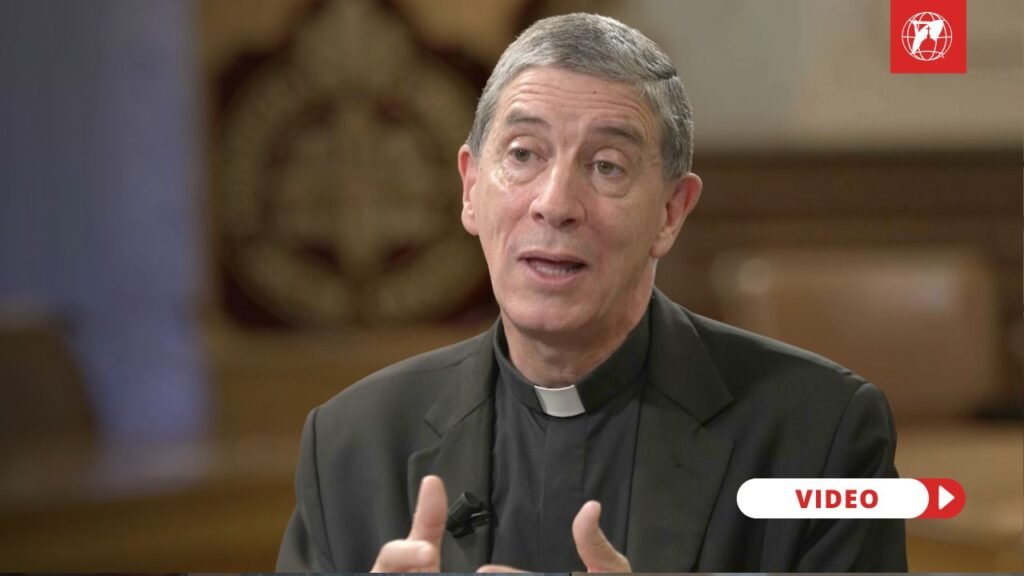

He was trained to heal with a scalpel — and later called to heal in the confessional. Father Wenceslao Vial is a priest and professor at the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross, and his work sits at the crossroads of medicine, psychology, and spiritual life.

Through books such as Psychology and Christian Life and his study of Viktor Frankl, Fr. Vial has spent years addressing a question many Catholics wrestle with: what belongs in therapy, and what belongs in confession.

In an interview with EWTN Vatican Correspondent Magdalena Wolińska-Riedi, he explains why the two are not rivals — but distinct forms of help, with different goals.

The Human Person Has Three Dimensions

Asked what it means for him to be both a confessor and a scholar of psychology and spiritual life, Fr. Vial said his experience in both worlds has clarified one essential truth: the human person cannot be reduced to only one part.

“It helps me because I get into what the dimensions of the human being are—that is, the human being must always be seen in three dimensions: organic, psychological, and spiritual. We cannot neglect any of them,” he said.

He noted that suffering often deepens when one of these dimensions is ignored. “Sometimes there are people who suffer greatly because they don’t take care of their body, or because they don’t take care of their psyche, or because they don’t take care of their spiritual dimension,” he explained.

And while the spiritual dimension includes the relationship with God and the voice of conscience, he stressed that it also includes the deeper questions people carry. “In the spiritual dimension we don’t only have the encounter with God or difficulties of conscience; we also have everything that refers to the search for the meaning of life and interpersonal relationships.”

What Confession Gives That Therapy Cannot

When Wolińska-Riedi asked how confession helps a person psychologically — and how psychology can help confessors — Fr. Vial emphasized that repentance itself has a real healing power.

“Confession and reconciliation seek forgiveness, and this is related to the person who confesses and repents, and repentance in itself has a healing power,” he said.

But he also insisted that sacramental confession offers something no therapist can provide, even at their best. When asked what confession gives that psychology cannot, Fr. Vial answered directly:

“The first thing it gives is forgiveness—that is, God’s forgiveness. No psychotherapy gives that; no psychotherapy puts a model of a person in front of you, whereas confession and spiritual accompaniment put Christ before you—in other words, that’s what it gives.”

He added that confession also gives what therapy cannot: “grace.” As he explained, “what it also gives is grace, God’s grace, that created supernatural good that helps us. In other words, it’s an interior force that transforms you, that converts you, and finally gives you peace.”

Different Goals, and the Need for Mutual Understanding

Therapy, Fr. Vial said, is not a lesser substitute for confession — it simply aims at something different. Asked whether therapy can offer something confession cannot, he explained that psychology and psychiatry seek stability and healing in the personality itself.

“The fact is that the goals are actually different,” he said. “Psychotherapy or psychology, or medical treatment, psychiatric treatment—I’m a doctor—gives the person something different. It gives or seeks psychological health, perhaps seeks to restore some difficulties of personality or way of being that exist or that come from even before birth.”

Because these two forms of help operate in different spheres, Fr. Vial warned that problems arise when either side becomes suspicious of the other.

“When there’s a lack of understanding between the two fields, when there’s a lack of knowledge, when the psychotherapist or psychologist or doctor distrusts spiritual life, or the priest, the confessor, distrusts psychology—that lack of knowledge causes distrust that goes against the person, against the good of the person, which is what is being sought,” he said.

For this reason, he argued that both roles require deep listening and humility. “The priest has to listen a lot, the psychotherapist has to listen a lot as well, and both must know the field in which the other operates, and thus help.”

When a “Confession” Is Really a Symptom

One of the most delicate moments in spiritual direction and confession comes when a penitent brings something that looks more like a symptom than a freely chosen act.

When asked how he handles culpability and absolution in these situations, Fr. Vial explained that discernment is crucial — and that the priest must proceed gently.

“This depends a lot on the situation you find yourself in,” he said. “But indeed, sometimes there’s a penitent who says something—well, this isn’t properly a sin, they’re not confessing something because it hurts them, because they’ve harmed themselves, because they’ve harmed others, because it pains God who loves us… Instead, they’re saying it perhaps through an obsessive mechanism.”

He described how obsessive anxiety can distort a person’s spiritual life, even turning confession into a cycle of fear rather than repentance. “A mechanism of anticipatory anxiety like the typical mechanism of obsession, right?” he said.

In those cases, he explained, the priest’s task is to listen first, and then help the person rediscover God’s love and the true meaning of sin. “The priest doesn’t have a ‘sin-ometer’ to see whether this is a sin or not, and neither does God,” he said.

What matters most, he insisted, is the Lord’s knowledge of the person. “What God seeks—and God knows everything, besides. If a person gets complicated, that’s the first thing you have to tell them. Look, God knows absolutely everything.”

A Research Group Born From Frankl and Rome

At the end of the interview, Wolińska-Riedi asked about a research group Fr. Vial founded at the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross, dedicated to studying psychology and spiritual life together.

Fr. Vial explained that the group is called Juan Bautista Torelló, named after a priest and psychiatrist who taught at the university and died in 2011. “He was a very good friend of Viktor Frankl,” he said.

He recalled that in 1970, Torelló brought Frankl to Rome, introduced him to Pope Paul VI, and helped arrange a meeting that left a deep impression on the famous psychiatrist.

Today, Fr. Vial said, the goal of the group is to explore what Torelló understood decades ago: the relationship between psychology and spiritual life is not a competition, but a meeting point.

“For a long time it has been thought that they were distant fields, even contrary to each other, when in fact they are very intertwined,” he said. “We have to see them together.”

Adapted by Jacob Stein. Produced by Alexey Gotovskiy; Camera by Alberto Basile, Fabio Gonnella; Video edited by Andrea Manna.